Starting Your Seed Calendar

I think everyone loves the idea of growing from seed but most people are afraid to do it. It’s time to get over that fear—me included—mainly because they are much cheaper than buying plants at the store and are much more rewarding. There are also more varieties to choose from than what you’ll find in stores. But before you plant seeds it’s best to know when to plant them for the most success, and this is where a seed calendar comes in handy.

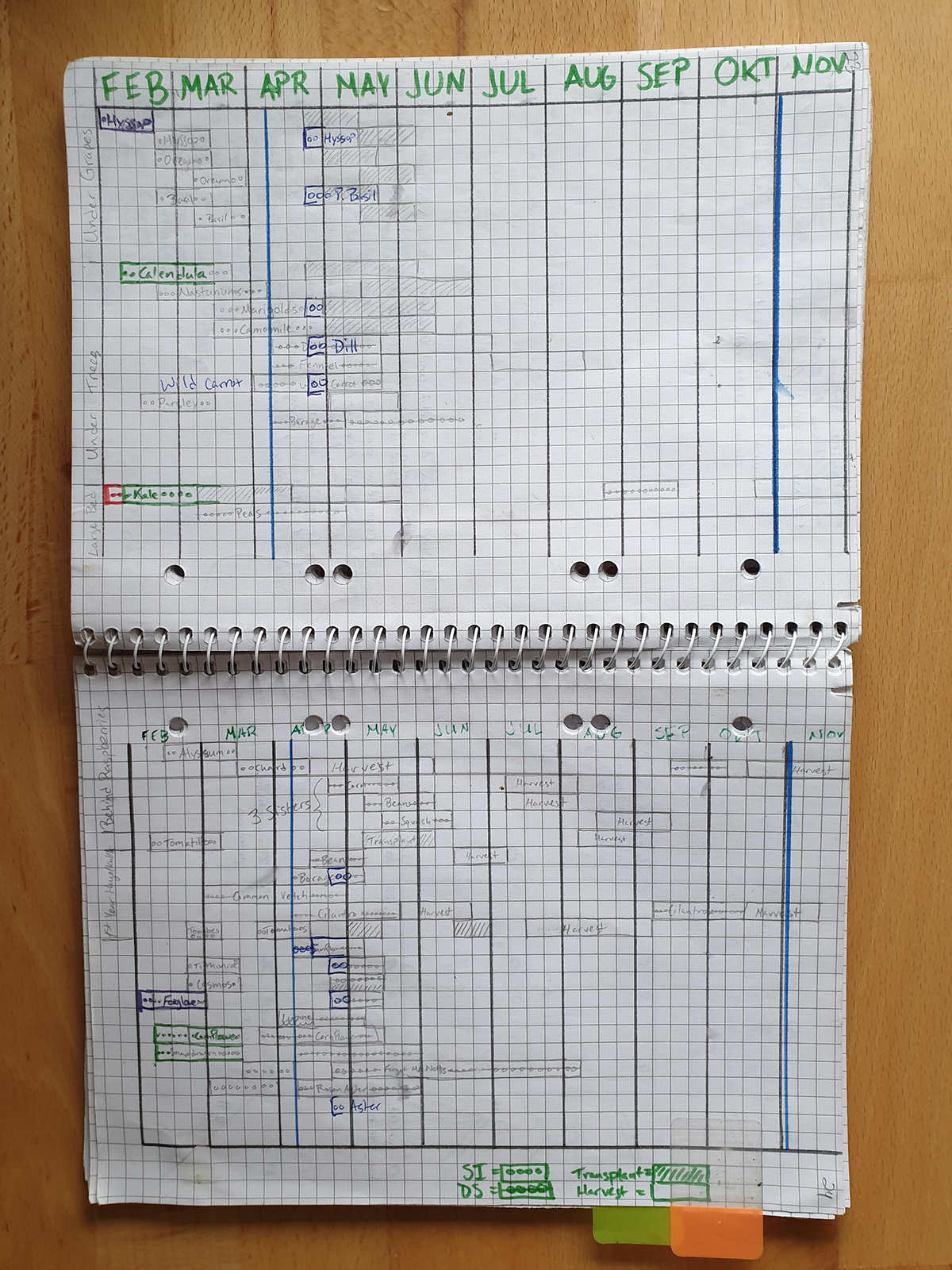

Seed calendars provide an overview of the year and organize when to sow the horde of seed packets we all have. It’s also a great way to visualize when to transplant and harvest.

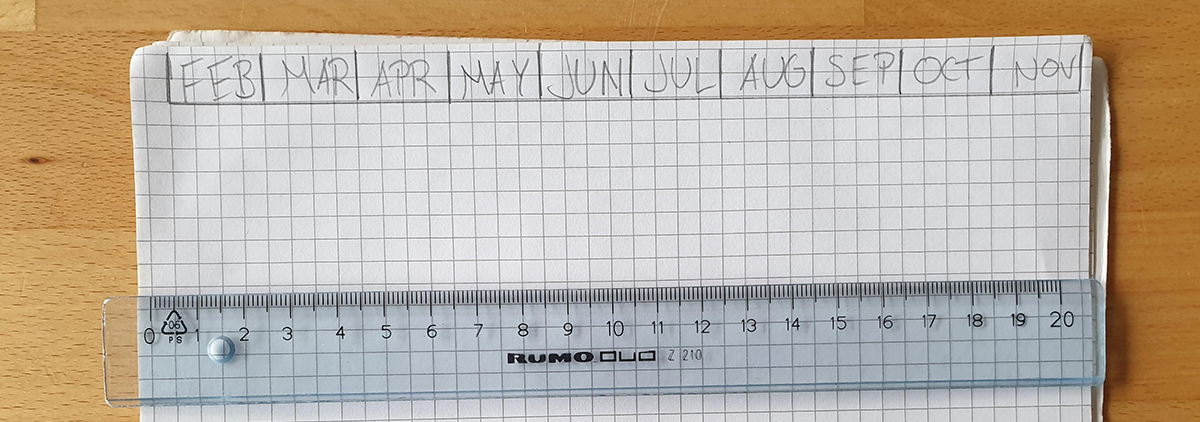

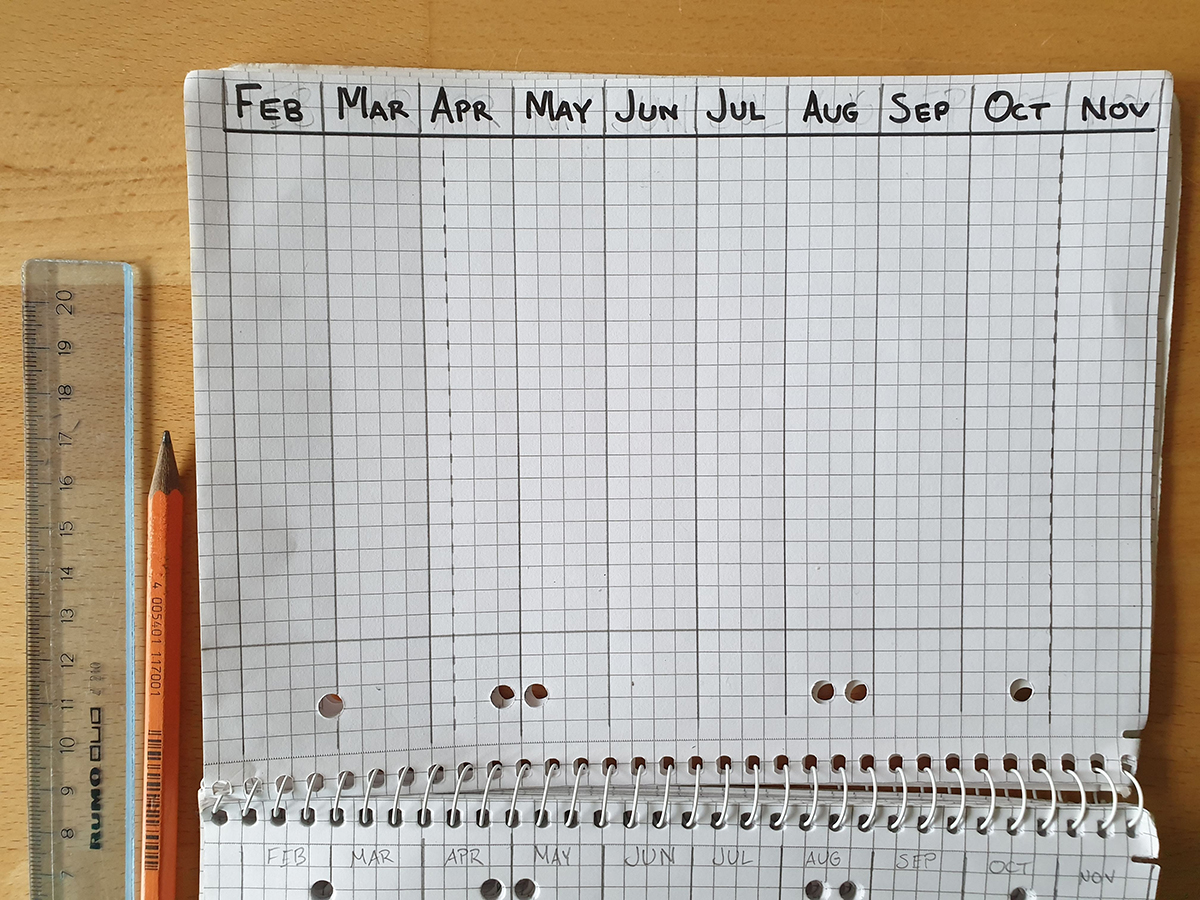

You’ll need a gridded piece of paper, a pencil, straight edge ruler, and a pen.

I created a calendar directly in my garden journal. Use 4 squares to represent the weeks for each month. The grid I’m using has 42 squares, limiting my calendar to 10 months. Not much sowing and transplanting occurs during December and January, so throw these months out if your grid is limited, too.

I recommend using a pencil so mistakes can be erased but a pen will work for this step too. Across the top of the page label every four squares with the appropriate month. Then use a ruler to draw straight lines down the page.

Now that the calendar is created, mark your first and last frost dates with a dotted line. US residents can find it here https://www.almanac.com/gardening/frostdates, but for everyone else, search for “average first and last frost, city and country” to find it. In the future, you could use a pen to record the year’s actual last and first frost dates and then use them as a reference for coming years.

On to the fun part, filling in the calendar! Gather your seed packets or seed list and begin reading the information. In Germany, seed packets list the recommended month for planting, but I prefer knowing the weeks or days before the last frost to be planted.

To be a good gardener, it’s best to start learning plants in terms of days or weeks growing so if you move to a different climate, the only info required are the frost days. Growth information is also helpful for succession planting, a way to extend a crop’s availability during the growing season in order to make efficient use of time and space. Do yourself a favor and familiarize yourself on days till harvest.

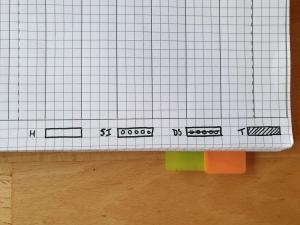

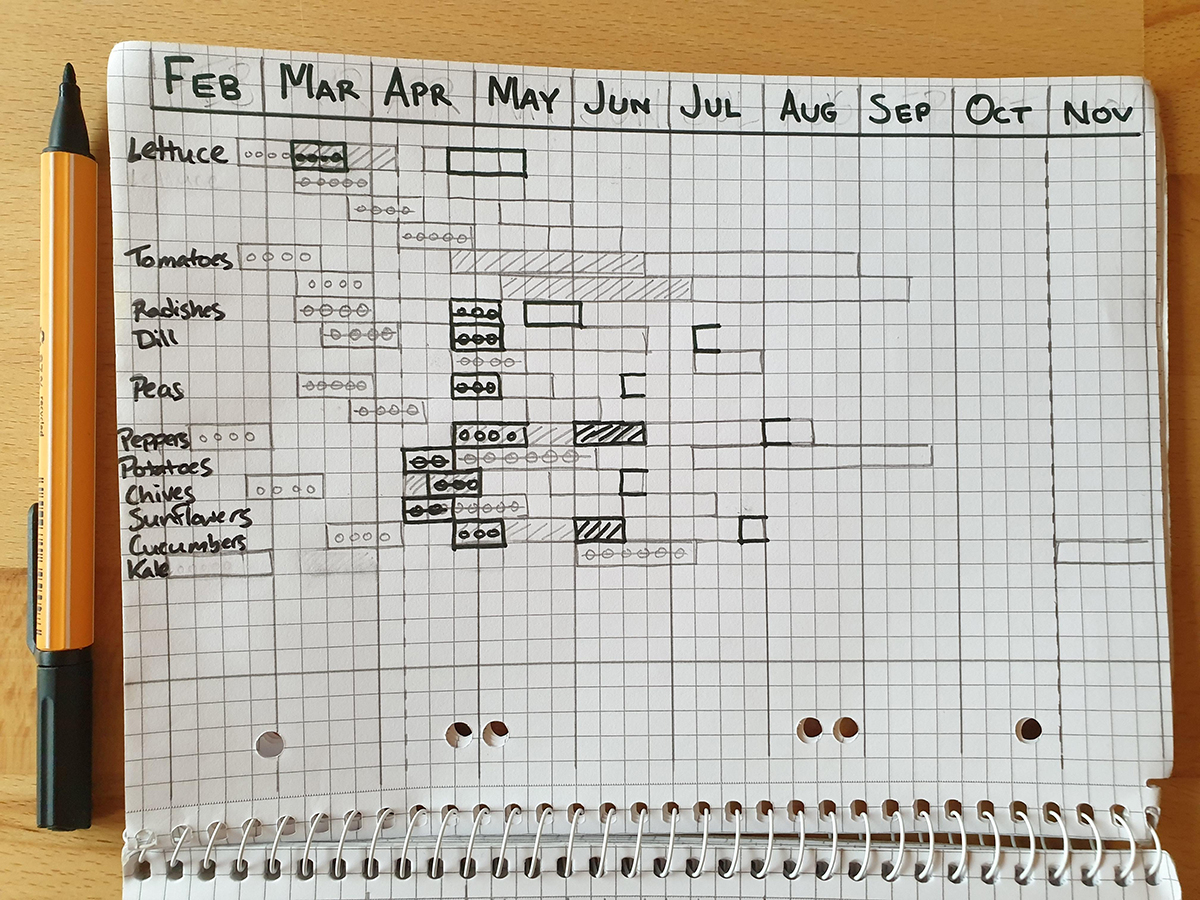

The symbols I use for the chart are: Harvest “H,” Sow Indoors “SI,” Direct Sow “DS” Transplant “T” By all means use whatever symbols and abbreviations you like; it’s your calendar, go ahead and personalize it.

Let’s use lettuce and tomatoes as examples.

Lettuce can be sown indoors 6 weeks before last frost, transplanted 4 weeks before last frost, or direct sown 4 weeks before last frost, then harvested in 40 days, roughly 1.5 months later. Using a pencil, write lettuce on the left side of your chart, find your frost date line then count 6 squares back from the line. For my area that means seeds can be sown at the earliest of the last week in February.

Create a rectangle for at least 3 weeks and mark with your “sow indoors” symbol—I use circles. This rectangle represents the earliest you can sow your seeds.

From the frost date line count four squares back and mark as earliest transplant time.

40 days till harvest, does that mean from sowing the seed or after transplanting? It depends: some seed companies clearly state whether it’s from sowing or after transplant so always read the seed packet or check the website. If it’s not clearly stated then the general rule is: if the seed is direct sown then it’s from the time of sowing; if the seedling is transplanted then it’s from the time after transplanting.

Plants can have a tendency to stop growing for short period of time after transplanting to adjust to the new soil biology. (As a side note, this pause in growth is when they are most vulnerable to pests.) 40 days is a little over five weeks. From your first transplant line count 5-6 squares forward. For me this would be the third week in April. Mark as “harvest.”

All this recording should be done in pencil so that when you do sow, it can be marked in pen. So let’s say there wasn’t much time to sow seeds during that last week in February, or you’ll be on vacation and didn’t sow your seeds until the second or third week of March. Mark when you actually sowed your seeds in pen or a different colored pencil, and shift the subsequent transplant and harvest times. And since you were late, you can now see on the calendar that the seeds could be sown directly outside if you don’t want to start them indoors.

A seed calendar is a guideline. It’s okay to be late: in fact, a general rule is that it’s better to be a little late than too early (unless it’s cold crops like radishes or kale).

To have lettuce from April - June consider succession planting. On the lines below offset the sowing and harvest dates. This way you’ll have a continuous supply for 2-3 months rather than only 1-2 weeks in April.

Tomatoes require a different strategy. Unless you live in a warm climate that rarely gets frost—say, southern Mexico and below—tomatoes must be started indoors. Tomatoes require roughly 120 days from seed to fruit. The growing season for my area here in Germany is roughly 190 days, 70 days extra… if there isn’t a sudden frost early or late in the season: tomatoes absolutely hate frost. Even though there’s a potential month of harvest at the end of season from direct sow to fruit, it’s too risky. Also, by starting early you can harvest tomatoes for up to 3 months earlier rather than in one month at the end of summer especially with succession planting or early varieties.

Sowing tomatoes indoors starts 6 weeks before the last frost—end of February. Earliest transplant to latest transplant 2-10 weeks after frost—end of April until end of June. Harvest 60 days or 8 weeks later—end of June until fall.

Again the calendar is a guideline, giving an overview of the year. If the weather was particularly cool after transplanting for warm weather crops, such as tomatoes, harvest might be in 70 or 80 days instead of 60.

The calendar is also useful if you’d like to cook a special dish made entirely of fruits or vegetables from your garden, such as ratatouille, especially if the plants are harvested at different times of the year. Or maybe, you want annual flowers in bloom for a special occasion like a wedding, birthday, or anniversary. Let’s say you know you’ll be on vacation during the normal tomato harvest: transplant the seedlings so the harvest will be before or after the trip. If you want the longest harvest possible for a particular vegetable look at early, mid, and late season varieties.

I should note that the calendar is not very useful if trying to manipulate perennial crops and flowers, such as fruiting trees, fruiting bushes, asparagus, artichokes, purple coneflowers etc,. They are fixed in the seasons and special early or late varieties are needed to extend the season. If you have space on the calendar after recording the annuals feel free to record your perennial harvest times. It’s your calendar, record whatever you like!

I hope this guide helps organize when to plant your seeds. It’s time to face our fears! For advice on the next step, come back for the next article, “How to sow seeds.”

- Filed to:

- Seeds

- Organization